|

The first few minutes of VOYAGER is

revealing of everything that is to

come. It opens black-and-white, outside a generic

50-ish airport populated by

generic 50-ish people and automobiles. The voyager shows

up, hugs this handsome woman

farewell, sits down in the utterly familiar waiting

room, and buries his head in

his hands in a sea of felt hats and cigarette smoke,

thinking of a certain woman

who no longer exists. He does not want to be there or

anywhere.

"What

was the use of looking anymore? There was nothing

for me to see. Her hands

that no longer existed anywhere, her movements as

she tossed the pony-tail

toward the back of her head, her teeth, her lips,

her eyes that no longer

existed anywhere -- where could I look for them?"

Then color filters back on screen as

the camera takes him two months back in

time, to another waiting room straight out of

faded photographs, poised to miss

another plane. Over and over again the film would

echo this strong sense of

spatial dislocation, address the circular nature of

time, narrate the story as

some sort of a chronicle of a death foretold and of

human endeavors foredoomed,

and enhance it with flashbacks and voice-overs by

someone precisely situated in

a certain period in history and thus make the events

twice removed from us, and do

all of these with plenty of sardonic humor and

self-irony. It is a good,

solid beginning for a much overlooked, excellent

film.

Sam Shepard plays the voyager, Walter Faber, a

globe-trotting American engineer

who sets his bearings by his faith in technology

and treats metaphysics as an

exercise in the laws of probability. He carries with him

a bored, presumptuous air

which of course makes him irresistible to women. We

watch him snatched and

shepherded aboard a gorgeous propeller plane, turn into

an entry in plane-crash

statistics, survive the landing, and become

witness to a suicide in a strange land - all

appropriately meaningless and

absurd, except that they call to him memories of a woman

he once knew before the war,

Hanna, whom he sees in crisp flashbacks. He returns to

civilization, haunted by

memories.

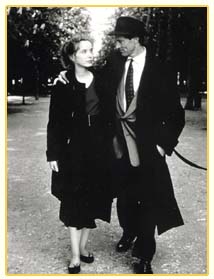

The "train of coincidence" runs on; he hops on a boat to

France to escape a female acquaintance and to

resume his anonymous, moment-to-moment existence atop

the bell-shaped curve. Instead, he runs into a young

woman he names "Sabeth" who reminds him of

his lost love. She is something of a paradox,

this Sabeth, terribly young and

vulnerable, a lover of ancient art and its

timeless mysteries, and at the same

time devoted to Camus and Sartre, those

unabashedly contemporary writers who

write of freedom and transparency and of

experiences created ex-nihilo,

unencumbered by a troublesome past. He sees her a lot,

and there are some delicate

scenes of glances exchanged in crowded ballrooms and

slow-dancing on the moonlit

deck. (The soundtrack is moody but very pretty.)

Stranded on an oceanliner in

the middle of the Atlantic, the voyager who shuns

entanglements finds himself

locked on to this young woman, a beckon that arose from

the depths of his past and

destined to guide him to complete an act of destruction

he set into motion some twenty years ago.

They land in Paris where Faber delivers speeches on the

Future of Mankind and stalks

Sabeth in art museums. They encounter the inevitable

scuffles in Parisian cafes and

graffiti protesting the Algerian war. The heart of the

film consists of the couple's

journey across the continent, from metropolitan Paris,

through blazing wheat-fields in the south of

France, to nameless historic Roman

ruins in Florence and Rome, finally to arrive at

the ancient villages of

Greece. Along the way are scattered sequences of great

tenderness and discipline

graced with extremely evocative camera work.

In Athens they are touched by tragedy and reunite with

Hanna; swiftly unfolding

events bridge the twenty years that separates them, and

simultaneously the memories that has been

tormenting Faber passes into the

present. The acting is particularly impressive in

this more somber half of the

film: e.g,. Delpy's Sabeth sitting dry-eyed and crushed

in the cafe where Faber left

her; Shepard and Barbara Sukowa's Hanna maneuvering to

wait each other out over

dinner; it is all quite extraordinarily restrained and

dignified.

There is something about the adaptation (or maybe it is

the cinematography) that makes

the tale's symbolic dimension leap off the screen and

highlights the cyclic quality

of this improbable tale of strong-willed, self-centered

people forging their fate only

to get ensnared by it. Yet the characters never come

across as mere mechanical parts reenacting an

ancient drama, nor do Faber's

relations with Sabeth or Hanna seem at any time less

than genuine.

|