|

Claudia Steinberg: Could

you talk about your current project, Max Frischís

"Homo Faber"?

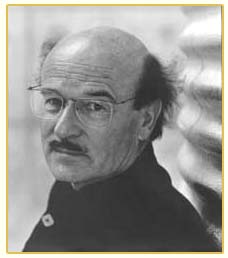

Volker Schlondorff:

The novel starts in Central America and then the hero

goes on a boat trip to Europe and then he travels from

Paris to Athens, crisscrossing Europe.

We just follow his travels. Itís a real road

movie, which is a nightmare for every production manager

who has to book all the flights and hotel rooms and see

that everybody is there all the time. Half the budget

goes into the traveling expenses. Our main actor, Sam

Shepard, doesnít fly, so we

have to drive him everywhere. Right now he is on a train

from his hometown of

Charlottesville, Virginia, to Los Angeles. Heíll get

there in two days. Then weíll

shoot there for a few days and then it will take him

almost a week to go to Mexico,

and from there, heíll drive to

New York, which will take him, we hope, about six days.

CS You did know about that beforehand, didnít you?

VS Yes, I did, but I took him anyhow, because I thought

he was the right choice for the part and it gives me a

little time to breathe in between the different

sections.

CS Sam Shepard will take the boat to Europe?

VS There are no boats anymore, just one freight liner

every week, but it takes two weeks to cross the

Atlantic. On the other hand, he wanted the part so badly

that he agreed to take the Concorde from New York to

Paris. Itís not that he is afraid of flying, he is

afraid of being locked into a machine for hours on end.

Iím just the opposite. At least once a month I go back

and forth from Europe to America. Thatís

what I have done for the last five years and jetlag is

my permanent condition. However,

I do have the highest esteem for someone, who says, ďI

have the same number of years to live as you do but Iíll

take my time moving from one place to another.Ē I think

he is working in-between, especially when he is on a

train, he can write well.

CS How does it feel to work with Shepard, an actor who

is also a serious writer?

VS It is very comforting to have him on the set. I wrote

the screenplay myself with Rudi Wurlizer, adapting it

from the novel, but in English, a language that is not

my own. So to have a writer there, who does not respond

as an actor to the material but as a writer is quite

reassuring.

CS Would you allow him to make any changes?

VS I trust his instincts, but you donít change on the

set, because youíre just too busy making your movie. But

in the weeks of preparations and rehearsals,

he did not actually rewrite any of the dialogue. He

pointed to areas that he thought were strongÖ he

stimulated us.

CS Max Frisch, the author of Homo Faber, wanted you as a

director for his book?

VS He had been selling the rights to this book for 25

years, so it was always being optioned by someone and I

think he kind of gave up on it. It was a very

contemporary novel when it first appeared in 1957 and

now it is like a period piece. You have to have the

right cars and the right costumes. It might as well be a

film playing in the 1900s. We went to Italy, to France,

and we will have to change every street, every piece of

writing on the wall, every neon sign, and the

furnishings in the restaurants.

CS Is Homo Faber also done by an American producer?

VS No, itís strictly a European production, a

French/German co-production.

CS Did Max Frisch have any input as far as the

screenplay is concerned?

VS He is a very demanding writer and wouldnít give the

rights without regards to the screenplay. But I always

love to consult with the writer anyway. |