|

How the late playwright, actor, author and

screenwriter's vast canon works as a meditation on life,

masculinity, mythology and the destiny of the United

States

"I hate endings," Sam Shepard declared to Carol Rosen in

an interview in 1991. "Endings are just a pain in the

ass". Shepard's own ending, with his death from

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis also known as Lou

Gehrig's Disease at the age of 73, is especially hard

to take, given his prodigious and ongoing effect upon

American theatre, literature and film.

The archive of work left by Shepard is extraordinary in

its formal range and its creative experimentation. In

addition to writing some 44 plays, numerous film

screenplays and several collections of short fiction, he

accrued almost 70 credits as a screen actor. The stage

works themselves are multitudinous rather than singular

in design, frequently having more in common with

artistic collage or jazz improvisation than with the

tradition of the well-made play taking one example

only, Tongues, in 1978, is subtitled: "A piece for voice

and percussion".

How to make sense of this vast, eclectic corpus? Here we

may resemble Shelly, a character in Shepard's play

"Buried Child" (1978), who struggles to sift all the

information given her: "I'm just trying to put all this

together." It is also important to reckon with US critic

Richard Gilman's claim that Shepard's work is

"extraordinarily resistant to thematic exegesis".

Nevertheless, the plays, stories, screenplays and

performances can be put together tactfully and assessed

as a sustained meditation on American masculinity, the

mythology of the American West and the destiny of the

United States.

Shepard's career often recycled imagery of the

traditional American frontiersman: consider such screen

roles as the heroic test pilot Chuck Yeager in "The

Right Stuff" (1983) or the taciturn FBI agent in "Thunderheart"

(1992).

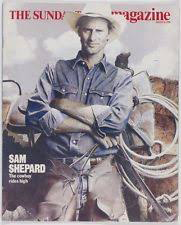

Or recall Annie Leibovitz's 1984 photograph in which,

fully equipped with cowboy paraphernalia of Stetson,

denims, chaps and lasso, Shepard looks down upon the

humbled spectator.

Shepard's writing, however, engages in complex fashion

with the condition of American masculinity. Interviewed

by The New York Times, he observed that in the wake of

the closing of the frontier, "the American male is on a

very bad trip". His plays and film scripts are most

absorbed by these damaged or depleted patriarchs. And it

is a moot point whether the decay of pioneer masculinity

evidenced, for instance, by Eddie's "peculiar

broken-down quality" in "Fool for Love" (1983) is

cause for celebration or occasion for lament.

Nevertheless, Shepard's self-consciousness is such that

traditional US masculinity is often scrutinised even

satirised in his drama. Frontier ruggedness appears

risible and parodic when shown still circulating in an

America of suburbia, television and plastic; there is

something ridiculous about Ellis's declaration in "Curse

of the Starving Class" (1976) that: "I'm a steak man.

'Meat and blood', that's my motto." If women are

sometimes impoverished presences in Shepard's writing,

they still have moments in which they pierce through

such masculine nostalgia. As May demands in "Fool for

Love", on hearing Eddie's proposal that they decamp to

Wyoming: "What's up there? Marlboro Men?"

Not for nothing was Shepard's first stage play, written

in 1964, called "Cowboys". The figure of the cowboy

recurs across his work, but like Clint Eastwood in "Unforgiven"

(1992) or Richard Avedon in the photographs comprising

In the American West (1985), Shepard submits it to

interrogation rather than simple celebration. Lee in

"True West" (1980), for example, lives like a cowboy in

the desert not as existential choice but as a

consequence of social failure.

For Austin, Lee's brother, the region they inhabit can

no longer play its traditional role as source of

American redemption: the West is "a dead issue! It's

dried up". In much of his writing, Shepard reflects in

moods ranging from elegiac to sardonic upon the West's

exhaustion. Typical would be his screenplay for Wim

Wenders's film, "Paris, Texas" (1984): if the desert

with its promise persists here, it is increasingly

hemmed in by Houston's soulless spaces that range in

opulence from skyscrapers to peepshow booths.

Junk in Shepard's work is cultural as much as it is

material. For every rusting car or mouldering avocado,

there is a decaying image or narrative. Time and again,

his characters have as imaginative resources only

sedimented clichιs and pre-existing scripts, whether

derived from formula westerns (True West) or Gothic

potboilers (Buried Child). Cultural detritus is layered

so thickly as to make improbable any arrival at what a

character in "Buried Child" sardonically calls

"bedrock".

But if Shepard's version of America tends towards the

pessimistic, several counter-impulses suggest his

attachment still to utopia. One reason for cautious

optimism lies in the very openness of those endings with

which he struggled as a writer. Travis's destination as

he drives away from Houston at the end of "Paris, Texas"

is unscripted and unmapped termination is, if only for

a while, deferred.

|