|

The iconic actor and writer is in the midst of a

cultural moment with a new play opening, another one in

revival, and a book of fiction set in the American West

just out.

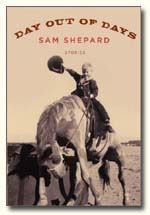

Once a cowboy always a cowboy? The cover of Sam

Shepard’s new story collection, Day Out of Days, shows a

family photo of little Sam at about 6, a fair-haired boy

on a horse many times his size waving a cowboy hat. You

can still feel the dusty air of the West in his work.

But Shepard is 66 now—strange but true. The chiseled,

movie-star face that made women swoony watching Days of

Heaven back in 1978 looks weathered. And this book and

his new play, Ages of the Moon (which opened last week

at the Atlantic Theater Company) tell us he’s hyperaware

of heading toward geezerville. The stories’ fictional,

Sam-like narrator criss-crosses the country’s highways,

stopping at motels, and wonders, “How does this happen?”

meaning life, aging, change. The two men in Ages of the

Moon are friends at the bitter end of middle age,

meeting in a country cabin to mourn their lost loves.

Who knows if Shepard’s feeling old these days? But no

one can call him worn-out.

Don’t worry, though. As a writer Shepard is not nearly

in the land of the has-been. These deceptively modest

works, reflective and witty, explode with fresh energy.

Their touches of absurdity give way to a depth of

emotional loss that will sneak up and wring your heart

dry. He’s still a star, still a treasure.

And we are having a Shepard moment. An off-Broadway

revival of A Lie of the Mind, one of his big plays about

loony violent families, is about to land in a production

loaded with indie-hip cred: directed by Ethan Hawke,

starring Keith Carradine and Josh Hamilton (previews

begin January 29).

Shepard's vintage plays hold up, but this is a moment to

appreciate his new works, of a piece with each other:

haunting stories a page or so long, a multi-layered,

two-character play that runs a swift hour and a quarter,

all about guys who have really lived.

His recent plays, The God of Hell and Kicking a Dead

Horse, had a vital political edge. Ages of the Moon is a

personal, character-driven piece, with the amazing,

hang-dog-faced Stephen Rea (has he ever overacted in his

life?) as Ames, who has called his white-haired pal

Byron (Irish actor Sean McGinley) to visit him. Ames is

in distress because his wife has bolted after learning

of his one-night stand with a woman Ames hardly

remembers.

Sitting on the porch, talking in the rhythms and with

the existential shrug of Beckett characters (“What are

we gonna do?” one of the them says. “There’s nothing to

do,” the other answers) they raise their glasses to

drink like a couple of synchronized swimmers. (The

production, which originated at the Abbey Theater in

Dublin, is directed with perfect timing by Jimmy Fay.)

In the flashier role, Rea gets to sing snatches of "King

of the Road" and "The Halls of Montezuma"; he takes a

rifle and shoots down an annoying ceiling fan, then

stares at it warily as if it’s some half-dead creature

that might jump up and bite him. There’s even a True

West-inflected brotherly wrestling match.

This play is wildly entertaining, yet in the end all the

chaos and fun can’t mask the heartbreaking sadness at

what both men have lost over time.

“You were head over heels,” Byron says of Ames and his

wife.

“I was,” Ames tells him. “I thought it would never end.”

That feeling—knocked out by the impermanence of love—is

echoed in the stories in Day Out of Days. A man whose

wife thinks he’s been cheating (we suspect he has too)

walks with her on the beach “remembering the days when

we were seldom out of each other’s sight and had no

reason to doubt we would be forever in love.”

The central character, on the road throughout these

stories, is not always the same man, but he has a

consistent, familiar voice. As in Shepard’s earlier

collections, these fictions tease, toying with

autobiography. The main character shares plenty with the

author. Sometimes he is an actor on a film set, like

Shepard, playing one more money-making small part as a

gruff military officer. Sometimes he has a son and

daughter with his longtime love. He has fraught memories of his

father. “I thought I had done my level best, done

everything I possibly could, not to become my father,”

one narrator says, only to get lost in a bottle of

tequila and have the old man turn up like an angry ghost

demanding Why?

While these pieces are rooted in the details of the

narrator’s travels, all those cramped rooms where he

lies, “listening to Highway 220 moaning right outside

the sliding glass door,” they often float gracefully

away from realism. The book’s epigraph is from Beckett,

who feels like the guiding spirit as the narrator

grapples with a sense of loss and disconnection, from

other people, even from himself. That dislocation takes

a physical shape in a series of stories about a man who

finds a talking severed head. A couple of those pieces

are told from the head’s point of view. The head

speculates that he and the man who picks him up “might

have become great pals” if the head hadn’t been

“completely cut off as I was.” Well, the Beckett quote

warns that there won’t be neat little stories here. And

that’s all good. Any old realist can give us lifelike

stories. It takes an eternally young genius like Shepard

to make us laugh and wonder what it would mean to be a

detached head, “yearning for home.”

“We used to be young and vigorous,” one of Shepard’s

narrators - a guy with an actual body - says. Who knows

if Shepard’s feeling old these days? But no can call him

worn-out.

|