|

“You change,” the playwright and actor Sam Shepard said. “You go through all

kinds of contortions. But the play is the same.”

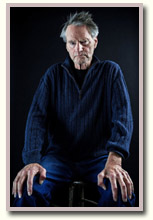

Mr. Shepard, 72, dressed in jeans, work boots, a ribbed sweater and a down vest,

was sitting on an upper floor of a Midtown rehearsal studio, its windows facing

the synthetic glamour of 42nd Street. He looked as if he’d rather be somewhere

else, a quieter place, a vaster one, with fewer flashing lights. He is still

strikingly handsome, with his cowboy mouth and sidewinder gaze, though he

describes himself as “craggy,”and his hands, the left one bearing a tattoo of a

quarter moon, are somewhat crabbed.

He has returned to New York for the New Group’s production of

“Buried Child,” a wrenching family drama — part comedy, part tragedy, part

mystery, part horror show — that exerts an astonishing hold on the actors who

have appeared in it. The play had its premiere at San Francisco’s Magic Theater

in the summer of 1978 and moved to New York a few months later. It won the

Pulitzer Prize for drama the next year and helped to transform Mr. Shepard from

a fringe writer to a major playwright. That’s a label he doesn’t necessarily

agree with.

“A lot of American playwrights seem to have a career as a playwright,” he said.

“I don’t consider it a career at all.”

And Mr. Shepard has never rested entirely easily with “Buried Child.” He rewrote

it for its 1996 Broadway debut, and now, 20 years later, even though he says the

play is unchanged, he is reworking and refining it — adding a joke here,

altering a word there. The characters, however, are still the same: Dodge and

Halie; their sons, Tilden and Bradley; and Tilden’s son Vince, who suddenly

arrives back at the Illinois homestead with his girlfriend, Shelly. Though Vince

believes he’s merely stopping in on his way across the country, the house and

its secrets won’t let him go so easily.

For the New Group revival, which begins performances on Tuesday, the director

Scott Elliott has assembled a cast including the married actors and longtime

Shepard collaborators Ed Harris and Amy Madigan as Dodge and Halie.

During his lunch break, Mr. Shepard spoke about theater, family and which of his

plays could use some work. These are edited excerpts from the conversation.

Q. Do you remember what image or impulse got “Buried Child” started?

It came from a newspaper article, actually. It had to do with an accidental

exhuming of a body, a child, in a backyard.

I understand this was the first play you ever rewrote, in rehearsals at the

Magic Theater in 1978. Why?

I listened to it, I guess. When you listen intensely to anything you see how it

can be improved. It’s a rhythmic thing. Like music. You can feel the way that

language lifts and turns around itself. The problematic character for me has

always been Vince. Because he’s closer to autobiography than anything else in

the play — everyone else is pieces, figments, fragments. Vince is more the guy

himself.

Has it become a different play as you’ve aged?

Not really. It remains the same clunky play.

One of the first plays to make a real impression on you was Eugene O’Neill’s

“Long Day’s Journey Into Night.”

It’s the greatest play ever written in America. But what I wanted to do was to

destroy the idea of the American family drama. It’s too psychological. Because

this and that happened, you wet the bed? Who cares? Who cares when there’s a

dead baby in the backyard?

Is the family still as central to your work? Your recent collaborations with

the Abbey Theater in Dublin — “Kicking a Dead Horse” and “Ages of the Moon” —

seemed to be moving away from it.

Well, the last thing we did was a variation of Oedipus. You can’t get any more

familial than Oedipus.

Do you think an outsider can ever really understand the dynamics of a family?

I remember as a kid, going into other people’s houses. Everything was different.

The smells in the kitchen were different; the clothing was different. That

bothered me. There’s something very mysterious about other families and the way

they function.

As a child, did you know that your family’s behavior wasn’t normative?

I thought this was all the way it was supposed to be. I remember a great friend

of mine in high school, he took me aside and he said, “I know your father was a

little off the deep end, but I didn’t know he was crazy.” And that sort of

shocked me a little bit.

You went on to have a volatile relationship with your father. When you had

your own children, did you try not to become your father?

Yes. It doesn’t help. You find these portions in you that are beyond the

psychological, beyond what you think you can control. And then suddenly you are

your father. You look at really old photographs, photographs that date back to

the 1800s, the bone structure of the face is pretty much implanted. Where does

it come from?

You’ve worked with Ed Harris often. What makes him a good actor for your

work?

He’s just a good actor. He’s handy, beyond handy. It’s very rare to find an

actor who’s as good onstage as they are in the movies.

Are you good on stage?

Not as good as I am in the movies. You don’t have to do anything in the movies.

You just sit there. Well, that’s not entirely true. You do less. I find the

whole situation of confronting an audience terrifying.

Have you ever had any sense of what makes an actor good in your work?

Adventure. An actor who’s willing to jump off the cliff, he’s going to go

anywhere.

What makes someone a good director for your work?

Somebody who leaves actors alone, who doesn’t interfere, who lets them play out

all the things they need to play out before they hit pay dirt.

What did you think of the recent Broadway revival of “Fool for Love”?

I thought the production was great. Good actors. The sound design was beautiful.

I was quite impressed with it. Especially in that theater. I thought that

theater would be too big for it. It wasn’t.

You still like that play?

Yeah.

Do you like all your plays?

No. There’s stuff you wish you’d spent more time on. Like “Curse of the Starving

Class.” Kind of raggedy.

Do you want to fix it?

Only in production. I wouldn’t go back and just rewrite something to be

rewriting it.

Where do you need to be — mentally, physically — to write?

Right at the heart of it. You wait, but you don’t wait too long, and then you

pounce and sit right in the middle of it. I’m working on a monologue now. At the

very beginning I thought, oh, if I wait a couple of days maybe more material

will come. But I didn’t, and I’m glad. More material would have come, but I

wouldn’t have written it down.

Can you write pretty much anywhere?

I used to. I used to write in the kitchen mostly. I wrote “Buried Child” in a

trailer at an old ranch house we had in California.

Where do you work now?

More and more by myself. Absolutely by myself. If there’s even a dog in the

room, I get a little nervous.

Can you write on a set anymore?

A little bit. Depending on the size of the role and how much distraction there

is. I can’t be changing costumes in the middle of writing. I do a lot of reading

instead. César Aira, Roberto Bolaño. I think the South Americans are head and

shoulders above North Americans in terms of fiction.

You’re so prolific — plays, fiction, film acting. Do you ever put aside work?

It’s difficult but important to do nothing if you can. You have to school

yourself.

What’s your version of doing nothing?

Sitting and watching the wall. Listening. Seeing light change.

Do you take vacations?

I’m always on vacation. I know that I have to finish certain things. So I have

obligations in a way. But not to a landlord, not to a boss.

So you’re your own boss. Are you too stern?

I demand too much.

You’re often spoken of as the greatest living American playwright. Do you

feel you’ve achieved something substantial?

Yes and no. If you include the short stories and all the other books and you

mash them up with some plays and stuff, then, yes, I’ve come at least close to

what I’m shooting for. In one individual piece, I’d say no. There are certainly

some plays I like better than others, but none that measure up.

|