|

|

|

Reviews for the Abbey Theatre

performance at the Peacock Theatre, Dublin, Ireland -

March 12 to April 14, 2007 |

|

|

|

|

|

Edel Coffey, Sunday Tribune - How

Shepard and Rea tamed the wild west

Sam Shepard's new play "Kicking A Dead Horse" was

written especially for Stephen Rea, which must be one of

the highest compliments an actor can be paid, especially

by a playwright who is considered one of the best of his

generation. The world premiere took place on Thursday

night in the Peacock theatre and seemed a strangely

muted affair, despite the momentousness of the event.

The play tells the story of Hobart Struther, a wealthy

New York art dealer, who has ditched his shiny city life

in search of authenticity in the modern-day wild west.

It begins with the absurdist sense of comedy that

Shepard has become known for.

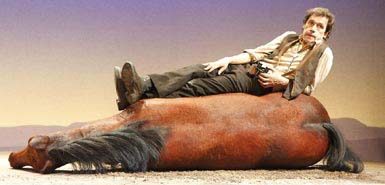

The set is covered with a sky-blue silk sheet, obscuring

oddlyshaped mounds. As the music rises, the sheet is

pulled slowly from the side of the stage to reveal

mounds of earth, a deep pit and a dead horse (which

looks very real). The audience titters.

From the pit in the centre of the stage, a spadeful of

dusty muck gets thrown out, followed by a subterranean

grunt, then another spadeful, another grunt, another

spadeful, until the spade gets thrown up and a dusty Rea

slowly emerges.

The first few minutes of the play are all physical

comedy; he gives the horse a good kick (he does this

several times throughout the play) before starting into

his monologue, which is so well-performed and

well-written it keeps the audience riveted right through

to the end.

Shepard is de-romanticising the mythology of the

American cowboy. As night falls and Struther is stranded

in the desert with his bags, a faulty tent and the rain

and lightning flashing about him, it becomes apparent

that finding authenticity through some quixotic ideal is

not as easy as it might look. Struther tells himself,

"So this is the way you wind up - not like some gallant

bushwacker but flattened out babbling in the open

plains."

Shepard mocks him even further by reminding him of the

wife or partner that Struther has clearly left behind to

go on his one-man mission to find himself.

"She'd be fixing supper for you about now, wouldn't

she?" It all starts to sound very appealing and it

perfectly lampoons the idea of city slickers trying to

find authenticity in their lives through the cowboy

dream.

There are political overtones and undertones to the

play, although they are so subtle they might not exist

at all. There are ambiguous lines that could refer to

the current political situation in America. These lines

resonate beyond the play itself, as when Struther

berates himself - "What the hell did you expect?" or

when he is finding his present predicament more

difficult than he expected, he says, "I do not

understand why I'm having so much trouble taming the

wild.

I've done this already. Haven't I already been through

all this?"

Amidst all the clever humour, there is a lot being dealt

with here- the search for some 'authenticity' in life,

the loneliness and fearfulness of growing old, and the

importance of companionship, "company, some warmth".

It's hard not to look at it through an autobiographical

filter, with the character Struther and Shepard being

the same age.

Shepard has said about Rea that he is "so malleable, he

can move in so many different directions" and it is true

that Rea gives a wonderful and completely unexpected

performance as Struther, from the surprise of the voice

to the relish with which he carries out the physical

comedy.

Paula Shields,The Observer -

Remains of the neigh:

Stephen Rea's Hobart Struther is talking to himself.

Stranded in the middle of nowhere in Sam Shepard's

mythic Midwest, with a dead horse for company, is an

edgy proposition for an ageing New York art dealer of

nervous disposition. Shepard's new play revisits

familiar themes: the constructs of America and the self,

the fictions we live by, individually and collectively.

Struther has left his successful East Coast life behind

in search of a more authentic experience on a trip out

West, but the death of his horse throws an equally

absurd light on this notion too.

Rea deftly inhabits the role of an older man driven to

make meaning of his existence. With comic skills to

match the mordant humour of his situation, he brings

numerous characters to life, when he isn't grappling

with a commendably realistic dead horse prop and

deadpanning the author's in-jokes at the audience.

Little wonder Shepard wrote this lyrical, mature play

with Rea in mind.

The mood darkens as the focus moves

from the personal to the political in an angry passage

that sums up the US, from the pioneers to today, in a

deconstruction of the American Dream: 'Destroyed

education. Turned our children into criminals.

Demolished art. Invaded sovereign nations. What else can

we do?'

Emer O'Kelly, Sunday Independent:

Hobart Struther is a man in trouble. A successful New

York art dealer in early American paintings, he feels

himself out of touch with the reality in the art. So he

has taken himself out of his Park Avenue apartment, out

of New York, to trek as the pioneers did in the desert:

on horseback. And the horse has upped and died on him

miles from anywhere.

Sam Shepard's "Kicking a Dead Horse" opens with Hobart

digging a grave for the horse. As he digs, he converses

with himself about reality and authenticity and how its

loss numbs the soul into a comfortable, deadly

detachment.

But as the monologue continues, we realise that there is

more: she is gone. Maybe his wife, maybe his mistress,

maybe both. And maybe all of this is fantasy: Hobart may

well be having the conversation from the comfort of his

armchair, his disgust at the destruction of everything

fine that he believes the United States stood for less a

grand gesture than a snoozing reminiscence in front of

the TV triggered by loneliness and fear of the passing

of time. Maybe this is a journey through death. At least

that seems to be the case when a young woman rises from

the grave to return Hobart's hat which he has thrown

into it.

The play is classic Shepard, rueful and paradoxic, and

the ending offers the blackest of comedy. In all of

that, it is highly entertaining. But clarity is missing,

and this may be because the author directs from a

position too close to his text. Are we dealing with an

elegy for the American Way? Are we dealing with a

denunciation of comfortable success? Or are we watching

a piece of surreal snook-cocking?

Stephen Rea, a longtime collaborator of Shepard, gives a

splendidly wry performance as Hobart, although he is

rather younger than the stage directions for the

character to be in his mid-60s. But the production (a

world premiere at the Peacock) suffers badly from

inadequate technical management: the dead horse is

unconvincing, and extreme suspension of disbelief is

required when it finally falls across its grave, failing

dismally to achieve what the action has been leading up

to.

Fergal O'Brien (Bloomberg.com) -

Sam Shepard Does Beckett, U.S.-Style, and the Hero's a

Cowboy:

Sam Shepard is premiering his new

play, "Kicking a Dead Horse,'" in Dublin. It's an

entirely suitable decision considering how much the work

owes to Beckett.

From the solitary character in a desolate landscape to

the sense of failure and the moments of absurdity, the

spirit of Beckett hangs over the production. Given the

emphasis on hopelessness, from the title to the closing

moments, it's fitting.

Stephen Rea is Hobart Struther, a New York art dealer

who pillaged the American West for paintings that he

sold on at inflated prices. But "things come back to

haunt you," he says, now stuck in that mythical West

after his horse dies.

Hobart's story, told as he tries to bury the horse in a

hole that's too small, is one of failure, loneliness and

running out of time. Rea, moving from anger to despair,

with some comical head turns and farcical attacks on the

dead equine in between, gives a compelling performance.

The Northern Ireland-born actor, for whom Shepard wrote

the role, has pushed the dour manner that normally

dominates his film work to the background, bringing a

subtle energy to his character, a man who wishes he was

a cowboy. (He has the spurs and the hat.)

A storm and his failure to raise a tent prompt Struther

to say: "I do not understand why I am having so much

trouble taming the wild." It could just as easily be

about Shepard, who has had the cowboy tag imposed on him

since early in his career, and we may assume an element

of autobiography in Struther's predicament.

The only other character, and the weakest element in the

play, is a young woman (Joanne Crawford) who appears

midway through the narrative, unseen by Struthers, and

returns his hat to him from the grave. Her meaning is

unclear, and it's a distracting and meaningless role. A

pity, because almost everything else, from Shepard's

direction to Brien Vahey's set, is hard to fault.

The play moves from the personal to the political in a

potted and damning history of the U.S. by Struther. As

with much I've read, listened to or watched this year,

touching on politics seems always to lead to one issue,

U.S. foreign policy and the Iraq war.

So, after Arcade Fire drew on images of holy wars in

"Neon Bible," and Iain Banks used "The Steep Approach to

Garbadale" to rant about the "great American people" for

"electing idiots," we have Shepard describing a country

that's gone from killing buffalo to destroying education

and invading sovereign nations.

The interesting thing is that Shepard doesn't push the

issue. It's just one element in a litany of the nation's

failures.

What you're left with is the feeling that the bad guys

are winning. Struther/Shepard is up against too many

things. And that's depressing, isn't it? Nobody wants

the cowboy to quit.

John Murray Brown, The Financial Times -

American angst in a desert landscape:

As the curtain rises on Sam Shepard's new play, another

gritty cowboy drama at first seems in prospect. Many of

his best known works have been set in a neon-lit world

of trailer-trash, dingy diners and strong men with

strong emotions - characters and props deployed to

explain what he sees as the sickness of modern America.

Shepard, who is also an accomplished stage and film

actor, is a giant of modern American theatre. From the

1960s along with writers such as Edward Albee, he

pioneered a new language, poetic yet rooted in the

landscape of the West - the True West, as the ironic

title of his best-known play describes it.

But "Kicking a Dead Horse", which was given its world

premiere on Thursday at Dublin's Peacock Theatre, feels

different. First the whimsical title. Non-American

audiences might grasp the drift more easily if "kicking"

were replaced by "flogging". Is this Shepard, in self

referential mode, responding to criticism for

"over-mining" his favourite settings of outback angst?

But the play's title is not just metaphorical, it is, as

we quickly discover, literal and real. This latest

Shepard work, which the writer directs himself, owes as

much to Samuel Beckett - the Irish playwright who is one

of his acknowledged influences - and to European

expressionist theatre as to the American road movie.

The setting is a desert landscape somewhere in the

American West. A dead horse takes up the centre of the

stage. A man is heard digging in a large pit nearby.

This looks and feels more like Godot than Hamlet.

Hobart Struther, played by Stephen Rea - for whom the

play was written and to whom it is dedicated - is not a

real cowboy as becomes apparent when rummaging through

his saddle bag he comes across his dental floss and his

can-opener.

Hobart is a businessman roughing it in the prairie for a

few days, in search of what he self-consciously calls

"authenticity". This is a key word in the play, repeated

several times and is an expression of Shepard's own

search for an authentic language and idiom to describe

modern America.

Hobart, like Shepard, is a man in his 60s. Unlike the

still boyish playwright, Hobart is starting to feel his

age. He has been through some sort of mental breakdown.

His marriage is under strain. He is someone once

familiar with working horses, but now a celebrated art

dealer in New York.

He collects what he calls "masterful western murals

nobody could recognise any more through the piled-up

years of grime, tobacco juice and bar-room brawl blood".

But now those "masterpieces" have become his "demons

trapping me in a life I wasn't meant for".

Hobart's commercial success mirrors the success of those

early pioneers, who like him, got rich plundering the

wilderness of the West. He has few illusions that this

was a bloody conquest. But as he recalls their exploits,

he also puzzles over the story of one pioneer who, not

content with a single suicide bullet, shot himself with

two pistols one to the head and one to the stomach.

"What was he thinking? To wind up like that after the

greatest expedition in the history of . . . Maybe he

realised something."

Shepard's last play, "The God of Hell" in 2004, was

poorly received by the critics, some dismissing it as

little more than a vehicle for a blunt-edged attack on

the Bush regime. It is tempting to see a political

impulse in this latest work too - a plea that the US

administration might reach some point of self knowledge

and recognise it is "kicking a dead horse" in Iraq.

There are several references that seem to link the

events in this remote desert badlands with another

desert country across the Blue Atlantic where Americans

are making a mess of things.

At one point Hobart talksof the early pioneers "invading

sovereign nations" by which he means the Indian tribes,

but Shepard may also be making an allusion to Iraq.

Yet just as the horse will not fit into the pit that

Hobart has dug for it, Shepard may also be warning the

audience against attempting to cast his message about

America and its history and landscape directly in the

context of the bloody events of Iraq.

Helen Boylan, Sunday Business

Post:

The various complex cowboys that have

peopled Sam Shepard’s plays have turned the abstract

fantasy of the Wild West on its head, making a mockery

of the idea that authenticity might be found beyond the

desert’s horizon.

In his latest play Kicking a Dead Horse, a one-man show

receiving its world premiere at the Abbey Theatre,

Shepard attempts a similar process of demystification.

However, Hobart Struther (played by Stephen Rea) is an

ill-conceived cowboy character, and his doomed quest for

authenticity fails to find the ring of truth.

Struther is a cowboy-turned-art dealer who has returned

to the desert, ‘‘hankering after a sense of being in his

own skin’’.

His horse has just died, and in the empty endless desert

landscape Struther is forced to confront the harsh

physical reality of cowboy life and the artificiality of

his cowboy dreams.

Despite self-conscious lighting cues and theatrical

jokes addressed directly to the audience, the monologue

form of the play is distinctly untheatrical.

The dramaturgical device of an alter-ego interrogating

the stranded Struther is clunky and unclear, while the

spontaneous appearance of a scantily clad woman with a

rescued cowboy hat is indulgent.

Meanwhile, the stunning visual aspect of Brien Vahey’s

tilted set (complete with life-size dead horse sculpted

by Padraig McGoran and John O’Connor) fails to

compensate for a stage scenario entirely lacking in

atmosphere.

Rea, returning to the Irish stage after ten years, still

holds a commanding stage presence, his frozen hangdog

expression and his fixed sad eyes battling against the

agitated physicality of his lean body.

Yet while Rea, as Struther, sets out to save himself,

Rea’s performance cannot save the play. As Struther

striving to find his voice, Rea is utterly convincing,

but Shepard’s play, unfortunately, gives him nothing to

say.

While making some timely, if unoriginal, observations

about America’s historical legacy (contained in a single

short speech lamenting the American dream of manifest

destiny), the 70-minute piece is so underwritten that it

seems more like a fragment from Shepard’s famous Motel

Chronicles than a play.

As the latest theatrical offering from one of America’s

greatest living playwrights, Kicking a Dead Horse is a

big disappointment.

Shepard is not so much kicking a dead horse as milking

the illusion of America’s scared cultural cow for all

its worth.

Despite the celebrity appearance in this play, the one

star rating below goes to the horse.

Karen Fricker, Variety:

Sam Shepard's first new play since

2004, "Kicking a Dead Horse," is altogether a strange beast. And

that's not just the dead horse onstage. Some excellent deadpan

humor, delivered brilliantly by a refreshingly antic Stephen Rea;

autobiographical material that seems a halfhearted attempt on

Shepard's part to unload old creative baggage; and the incongruous

setting of Ireland's National Theater all add up to an evening that

feels like a somewhat misfired in-joke.

The lights come up on a circular

stage with two mounds of dirt, a rectangular hole, a pile of riding

tackle, and -- yup -- a very real-looking life-size dead horse. A

man emerges out of the hole, carrying a shovel. "Fucking horse.

Goddamn," he says to the audience, and then kicks the dead horse.

Literally.

We are in broad parodic territory

here; and initially Rea gets the tone just right. He is Hobart

Struther, a New York art dealer who headed out on a desert walkabout

to rediscover his "authenticity," only to have his horse keel over.

Homage is clearly being paid to Samuel Beckett at his most absurdly

comic, as Hobart tries and fails repeatedly to tip the horse into

the too-small grave.

The key artist Shepard is glossing

here, however, is himself. Hobart made his fortune reselling

paintings of the American West at a massive markup. "What I couldn't

see was how those old masterpieces would become like demons,

trapping me in a life I wasn't meant for," he says self-pityingly.

This and other references (to New

York, where Shepard now sometimes lives, and his wife's "golden

hair") make clear that Shepard is reflecting on his own career and

life, seeming to renounce his past creative patterns by sending them

up. But by invoking all his familiar themes -- the American West,

dreams of escape, tourism, violence -- Shepard re-inscribes them in

his work even as he claims to disavow them.

On one level, he knowingly nods to

what he's doing by making the classic Shepardian battle between self

and other an internal one: Hobart bickers constantly with himself,

another challenge Rea carries off with great skill (if with an

overly mobile pan-American accent).

But the legend simply protests too

much: if Shepard really wanted to "make a clean break" from the

dead-horse weight that is his cowboy-playwright image, then why

write another cowboy play? The entire effort is steeped in

solipsism, into which it starts to disappear.

The first sign that things are

going wrong is the brief appearance of a pretty young woman in a

short slip who gives Hobart back his discarded Stetson -- a possible

nod to feminist critiques of the treatment of women characters in

his plays. But this is a self-reflexive gag too far -- you can't

objectify women and pretend not to at the same time (something the

creative team may have begun to realize in the run up to production,

given that the printed playscript says the woman is meant to be

naked.) And when Hobart collapses on the horse's body, sobbing, his

crisis now seems to be intended seriously, a tonal about-face that

prompts the only bum note of Rea's performance.

This play is part of an ongoing

engagement with Shepard's work that saw a fine revival of "True

West" last year. But Ireland is an odd context for such a

self-referential work; it's unlikely that audiences will have the

knowledge required to fully grasp its apparently intended ironies.

Colin Murphy, Irish Independent -

Shepard is certainly not flogging a dead horse:

THE US is kicking a dead horse in

Iraq, the outcome of a misconceived adventure that was

supposed to be about taming the wild.

This could be what the renowned American playwright, Sam

Shepard, is talking about in his enigmatic new play,

'Kicking A Dead Horse', which was written for the Abbey.

Stephen Rea plays Hobart Struther, a beaten-down

American who has fled his bourgeois Park Avenue

art-dealing life for a long trek across the prairies, in

search of his former self.

A day into his trek, his horse keels over, and this is

how we encounter Hobart: stuck in the wilderness,

kicking his dead horse. (The horse is pretty lifelike,

and the desert setting is elegantly captured by Brien

Vahey's set and John Comiskey's lighting.)

Stephen Rea plays Hobart as a weary refugee from

American materialism, a man who, as he found his

fortune, lost his sense of himself. He is more pathetic

than tragic, and Rea ennobles him with a sense of

yearning and a restless energy that is captivating.

Hobart's task is to bury his horse, but he is defeated

by the size and awkwardness of the stiffened corpse,

which he can't fit into the grave he has dug. The

writing is razor sharp.

There are no polemics: these themes are treated

elliptically, in Hobart's lonesome ruminations. A witty

ending leaves an appreciative audience asking each

other, 'what did it mean?'

Luke Clancy, theloy.com:

Cowboys have often been recruited to

help American look at itself, its dreams, drives and

desires. Even when cooked up by writers with no

experience of the Wild West – such as Zane Grey, the New

York orthodontist turned author of Western stories – the

cowboys provide a powerful image of a restless, brave,

manly nation, ready to make the wilderness safe for

industrial meat production.

That little gap between the cowboy myth and those who

foster it crops up again in Sam Shepard's latest, an

uncanny, one-handed, modern-day Western, having its

world premier here, in a production directed by the

playwright-actor-director.

Hobart Struther (Stephen Rea) finds himself alone in the

desert with no way out but to walk. His horse has up and

died, and Hobart feels honour bound to bury it. As he

digs the pit, he raves at his misfortune and describes –

addressing the audience directly – how manifest destiny

brought him here.

And while the short terms causes of his predicament

relate to an accidentally-snorted muzzle-full of oats,

that is really only part of a grander crisis of in

American self-love, for which Struther is just a symbol.

But no matter how keenly Shepherd is feeling the decline

and fall of the US of A (hints about Iraq and Bushism

abound) it isn't easy to have much sympathy. Struther,

who turns out to be a New York art dealer specialising

in Western Art, has plundered everything he touched,

until you can't help feeling that it is not the workings

of existential absurdity that has left him lost,

friendless and isolated; he's simply getting his just

desserts.

More than usual here, Shepard seems to be writing in the

shadow of Samuel Beckett, whose surreal stages the set

here (designed by Brien Vahey and lit by John Comiskey)

recall. Even the play's title, acted out with gusto by

Rea repeatedly, has a Beckettian futility to it. Rea's

performance – irascible, raggedy, with a fine dust of

humour, but undeniably un-cowboyish – adds a final twist

to this knotty exploration of inauthenticity, even if

the actor's North of Ireland accent is expertly buried

beneath a soft Western drone.

|

| |

| Reviews for the

Almeida Performance - London, England - September 5-20,

2008 |

|

Sarah Hemming, Financial Times:

There is a flurry of horse activity on the London stage

at the moment. While the National Theatre’s revival of

"War Horse" brings back those uncannily lifelike

puppets, Sam Shepard’s new play at the Almeida also

features a life-size equine quadruped. But this noble

steed spends the play with his legs in the air, having

dropped dead before the action starts. His demise has

left his rider stranded in America’s badlands and

saddled with the unenviable task of burying the corpse.

It is a wonderful, tragicomic scenario, ripe with

potential. But unfortunately the play is strangely inert

– in spite of a marvellous performance from Stephen Rea

in Shepard’s own production (first seen at Dublin’s

Abbey Theatre).

Rea plays Hobart Struther, an art dealer rich from

selling paintings of the American West. Tired of his

futile life, he has set out on a “quest for

authenticity”, back to the landscapes of those images.

He has packed beans, water, even dental floss. But he

reckoned without his horse’s digestive system. He begins

the play shovelling dirt and goes on to chastise himself

for his folly, between strenuous efforts to shove the

beast into its grave.

The stark scenario and deliberate theatricality of the

piece recall Beckett, and the disconsolate Struther,

arguing with his alter ego and wrestling comically with

his physical circumstances, could be a distant relative

of Beckett’s characters. So too the metaphysical

implications of the play. But it also extends, and

mischievously comments on, Shepard’s own preoccupations

with the American West, with restlessness, authenticity

and masculinity. And Struther’s plight becomes symbolic

of contemporary America, caught in an uneasy

relationship with the past and with its image of itself.

It offers immense riches, then, yet in execution it

seems curiously contrived. What could be meaningful

symbolism – Struther burying his cowboy hat – seems

heavy-handed, and Struther as a character is

overburdened with significance. There is some wonderful

writing: tough, poetic and funny. And Rea is a joy, his

furrowed face as melancholy as that of a dog on a diet,

his gangly frame contorting itself as he wrestles with

his dead companion. But still the play, like the horse,

proves obstinately unmoving.

Nicholas de Jongh, Evening

Standard:

It should come as no great surprise that Sam

Shepard, whose plays often describe how the great

American dream has given way to all manner of nightmare,

should now be moving into Samuel Beckett territory.

I suspect this broody, 70-minute solo piece, whose

impact is blunted by the pervading glumness of Stephen

Rea’s performance, enjoys spiritual and thematic links

with Beckett’s masterpiece, Happy Days. In that

extraordinary, virtual monologue, with its heroine,

Winnie, eventually trapped up to her neck in sand, you

sense that not only one life but perhaps the whole world

is drawing to a close.

Shepard’s "Kicking a Dead Horse", recently premiered in

Dublin and just seen in New York, does not go that far

but the reverberating Beckettian echoes and affinities

proliferate. Designer Brien Vahey summons up wild west

prairie badlands, where nothing grows but silence.

Sheets are whipped away from undulating mounds to reveal

a life-like but very dead horse, lying on its side.

Then Stephen’s Rea’s Hobart Struther, a 65‑year-old art

dealer in a Stetson, stranded in nowhere’s midst, hauls

himself out of a pit, from which he has been shoveling

earth and into which he is weirdly obsessed that his

horse should be tipped. Realism’s boundaries are now set

to be breached.

Talking in rather Beckettian style to himself, as if

that self was another person, Hobart scans the empty

horizon through his binoculars and launches himself on a

reminiscent, stream of self-consciousness. He has left

his wife. From his Park Avenue he has hurled invaluable

works of art, discovered in saloons and barns.He is

crazily intent upon this voyage of self‑discovery, or

“authenticity” as he puts it, a task that involves

facing up to a lifetime’s regrets.

Rea, in Shepard’s muted but ultimately romantic

production, relishes Hobart’s jovial cynicism, his

emphatic bravado, his struggles to move the horse to its

grave. The limited, dramatic tension, though, is

dependent on a strong sub-textual sense that Hobart

becomes increasingly possessed by fear, grief and

alienation, as he faces up to “me and myself”.It is

these moods that an obstinately phlegmatic Rea quite

fails to evoke. John Comiskey’s atmospheric lighting

design injects flickers of excitement into a Shepard

play that for once fails to grapple with the personal

and public issues it raises.

Sam Marlowe, The Times:

The metaphorical horse into which Sam Shepard puts the

boot in his latest play may not be dead yet, but it’s

certainly seen some miles. This 70-minute work, written

for the actor Stephen Rea and first performed at the

Abbey Theatre in Dublin last year, is steeped in

American mythology and set in familiar Shepard

territory, the West. Shepard seems at times to be

railing against the very imagery with which he has

become so strongly associated — but that internal debate

makes the play almost as arid as the landscape it

inhabits.

Rea is Hobart Struther, a New York art dealer who has

strapped on his spurs, donned his stetson and ventured

into the badlands in search of the “authenticity”

missing from his antiseptic, air-conditioned city life.

But his quest has gone awry — his horse, having choked

on its oats, has abruptly died. Two mounds of earth, a

large hole, and the dead beast: that, in Shepard’s own

production, is the scene that greets us once the blue

silk that covers the stage is whisked away. The only

initial sign of Rea’s Hobart is the shovelfuls of dirt

flying from the hole in which he plans to bury the hefty

corpse.

The scene is faintly reminiscent of Hamlet but more

forcefully Beckettian, as are Hobart’s arguments with

his own alter ego — whom he voices in a prissy, nasal

whine — which recall the bickering of Hamm and Clov or

Didi and Gogo. Yet Shepard’s writing never achieves

poignant, poetic transcendence. Instead we get a banal

account of Hobart’s failed marriage, or a rant about

America’s historical and contemporary political

failings. Racism, cultural vandalism, bellicose foreign

policy — it’s all crammed into one clumsy climactic

speech.

The play’s gestural language can be equally

heavy-handed, as when Hobart flings his cowboy gear into

the horse’s grave in a rejection of degraded archetype.

Odd, vivid moments stir the imagination: remembering how

he made a killing flogging paintings he found hanging

unremarked in saloon bars, Hobart imagines all those

Wild West beasts and guns captured in oils mutinously

hemming him in, “nostrils flaring, Colt revolvers

blazing away”.

And Rea’s performance is typically compelling, his long,

craggy face and unhappy eyes as tragi-comic as a

clown’s, his rangy body bending with slapstick strain as

he battles to shift that mountain of horseflesh. But

he’s hampered by characterisation that lacks texture and

definition — though not so severely as Joanne Crawford,

who makes a brief, wordless appearance as unnamed Young

Woman wearing a flimsy slip and Hobart’s jettisoned hat.

What she represents is unclear, but she is the most

conspicuous contrivance in a piece that places the

well-worn under a burning sun and still winds up feeling

half-baked.

Nick Curtis, Evening Standard - Sam Shepard rides

into town:

New plays by Sam Shepard still have an enticing cachet,

so this British premiere — first seen at the Abbey

Theatre, Dublin, and then in New York — is something of

a coup for the Almeida, not least because Shepard

himself occupies the director’s chair.

"Kicking a Dead Horse" stars that fine, hangdog actor

Stephen Rea as Manhattan art dealer Hobart Struther who,

tired of selling romantic pictures of the American West

at a huge mark-up, has embarked on a horseback journey

of self-discovery in the desert. Unfortunately, his

horse dies, and the play sees Struther discussing his

life as he tries and repeatedly fails to tip its huge

corpse into a too-small grave. Symbolism, anyone?

Critics of the American production noted the debt that

this blackly comic, Sisyphean image owed to Samuel

Beckett. Yet it also represents a continuation of the

author’s own preoccupations, and possibly a comment upon

them.

Shepard’s work is riddled with cowboy imagery and often

concerned with “authenticity” and the ways in which

American reality — especially American masculinity —

falls short of its abiding myths. Like the brothers in

"True West", and the similar siblings in "The Late Henry

Moss" — the last Shepard play premiered at the Almeida,

in 2006 — Hobart is torn between trying to dig the truth

out about himself, or simply bury it. Here, there is

even a recurrence of that other Shepard staple, the

sultry woman in a slip familiar from works like "Fool

for Love".

The title of "Kicking a Dead Horse", though, may have

more personal relevance for Shepard. Does he feel that

he, like America, is burdened by myth? Is he tired of

kicking over the same old themes, again and again? Does

he feel that nobody is listening to his diagnoses of

American sickness? There are just 16 performances at the

Almeida to give us a chance to find out.

Susannah Clapp, The Observer:

"Kicking A Dead Horse" is American writing at its

posturing cowboy worst: Beckett in a stetson. This Abbey

Theatre production of Sam Shepard's play, written for

Stephen Rea, features a Manhattan art dealer who, having

chucked his canvases out of the window, decides to head

for the Badlands so that he can bray about Authenticity.

His horse (and who can blame him?) pops his horseshoes,

and spends the evening with his plastic-looking hoofs in

the air. A girl in a mini-dress comes up from a fissure

to simper. All Rea has to do is grumble. He does so with

lovely, lugubrious confidentiality, but it's impossible

to make these speeches interesting. Talk about flogging

a supine equine.

Michael Billington, The Guardian:

Sam Shepard's characters constantly dream of a vanished

American West; and the process reaches its terminal

fulfilment in this Beckettian monologue about a man and

his dead horse marooned in what I take to be Montana.

Superbly performed by Stephen Rea, the piece may not

tell us anything radically new about Shepard, but it

feels like the end of a lifetime's journey.

Rea plays Hobart Struther: a Park Avenue art-dealer who

has abandoned career and family to return to his native

soil in a doomed quest for "authenticity". Equipped with

tent and provisions, he finds his mission sabotaged by

the death of his horse. So, having dug a hole in which

to bury the animal, Hobart dwells on the futility of his

existence. Having become rich through looting saloons of

Remington and Russell paintings, he has lived to see the

myth of the old West turned into a museum artefact. And

in attempting to return to his roots, he falls

inexorably into a void.

We have been here before in Shepard's plays and there is

something a little too sedulously Beckettian about such

comic business as Hobart's struggles with a collapsing

tent. I was also puzzled by the emergence of a silent

young woman from the horse's prospective grave.

But the piece is filled with the indefinable poetry of

loss, and with the sense that Hobart's personal

corruption mirrors that of America itself. In a moving

speech, Hobart recalls how the taming of the West was

only achieved through the destruction of indigenous

cultures and the transformation of the natural

landscape.

The chief pleasure, however, lies in Rea's performance.

What he captures supremely is the character's mix of the

elegiac and the absurd. There is something wanly heroic

about his determination to bury his infuriating horse,

or about the way he gazes wistfully at his cowboy hat

before casting it into the grave. Yet, as he scuttles

about like Clov in "Endgame", or engages in endless

dialogues with his sceptical alter ego, Rea richly

conveys the ridiculousness of trying to recapture a lost

dream.

Written for Rea and Dublin's Abbey Theatre, Shepard's

self-directed monologue may sometimes feel like a

summation of his complex feelings, mixing yearning and

rage, about the American West. But the intensity of the

performance prevents you feeling that a dead horse,

while being kicked, is simultaneously being flogged.

Rhonda Koenig, The Independent:

Is he alone and unobserved? You bet. Hobart Struther is

in the American desert, digging a grave for the title

animal, with only the wind and rocks for company. Yet,

despite his need to conserve water and energy, Hobart

not only digs a huge hole but spends 80 minutes loudly

reminiscing, worrying, raging, and regretting. Since he

was created by Sam Shepard (who also directed) and is

embodied by Stephen Rea (for whom the play was written),

Hobart has a fair-sized claim on our attention. But it

does not take long before we realise that he could have

been originated by any number of angry old men,

lamenting their lost youth and strength as well as

America's and conflating the two.

Hobart's labour is intensified by the literary burden he

bears. His loneliness, his clowning, and his hole evoke

Beckett, but the Irish playwright's influence is at

least equalled by those of American novelists. While his

name evokes Lambert Strether, the unworldly middle-aged

man sent east by Henry James to grow up in The

Ambassadors, Hobart's situation – the result of a quest

for "authenticity" – brings to mind that of numberless

fictional Americans whose search for truth is stopped by

a bullet or worse.

Hobart has fled New York, leaving behind a wife who was

once "beyond authentic", but with whom he has long since

settled into a routine. The self-hatred of this former

cowhand has become so intense that he has been throwing

"masterful" million-dollar paintings out of the window

on to Park Avenue. So Hobart returns to the West, where

he began his career in art by cozening yokels out of

unregarded treasures, and broods on his and America's

crimes.

Banal and inflated though this is, Rea attacks it with

soul and skill. His voice, dry and pinched, cautiously

plays out the reins of his desperation, then harshly

yanks them back. But he is forever battling against the

perfunctory and self-pitying quality of the material.

Though some may interpret the final catastrophe as a

demonstration that even good, idealistic Americans are

doomed, Hobart's fate suggests more strongly an extreme

expression of the desire to retreat, sulking, and

pretend that one has died, or the world has. The last

action of Shepard's play may create an almighty bang,

but emotionally and philosophically his play ends with a

whimper.

Charles Spencer, The Telegraph:

In real time, this new play from the American dramatist

Sam Shepard lasts only 70 minutes, but it feels

immeasurably longer than that. Indeed, I began to wonder

whether I'd get out of the theatre alive or succumb to

death by chronic tedium. Shepard, revered by some as a

great chronicler of the dark side of the American dream,

though he has more often struck me as a glib and

slapdash writer, here appears to be offering a summary

of, and perhaps a valediction to, his life's work.

Yet again we are in the dramatist's beloved American

West, that mythic terrain where men were men, and life

was hard and pure and simple. Our hero, Hobart Struther,

in his sixties like Shepard, has made a fortune

collecting paintings of the Wild West, raiding "every

damn saloon, barn and attic west of the Missouri" to

pick up old cowboy pictures on the cheap before selling

them at a tidy profit. Living in luxury on New York's

Park Avenue with his wife, however, he has felt a

gathering discontent, and an urge to get back to his

roots and rediscover the "authenticity" of life in the

wild, one man and his horse, and the great wilderness.

The only trouble is that on his first day out, his

four-legged friend has died on him, and in Brien Vahey's

design, a strikingly realistic and undoubtedly deceased

equine quadruped dominates the stage.

In an interminable but not especially illuminating

monologue, Stephen Rea, who has a face rather like a

placid horse himself, kicks his defunct mount, argues

with himself, indulges in some predictable liberal guilt

about what the Americans have done to their own country

and other sovereign nations, and attempts to drag the

dead beast into the grave he has dug for him. The

impression is of a man who no longer feels a part of his

own land.

As our hero surveys the distant horizon and the light

suddenly changes at the flick of a switch, the show

often feels like Beckett's Happy Days with a sex change

and an American accent. But as it becomes clear that our

hero isn't going to get much further than his dead

horse, one realises that though Shepard may share some

of Beckett's bleakness, he has none of the Irish

writer's poetry and precious little of his wit.

Rea, by turns puzzled, frustrated and panicky, gives an

efficient performance in Shepard's own production, first

staged by Dublin's Gate Theatre. But this is acting that

relies on technical skill rather than the prompting of

the heart, and it left me entirely unmoved. Worse still,

the constant suspicion that one is watching an allegory

about America, and indeed Shepard's own career, with its

frequent plundering of American myths, makes the whole

piece seem punishingly contrived.

Never mind the horse, it's this dead play that deserves

a kicking. |

| |

| |

|